Think of the HPLC Column as the Heart of

the HPLC System. It's the component where the actual separation of the

components in your mixture takes place.

Simple Analogy: Imagine a crowd of people (your sample mixture) running through a

forest (the column). People who stop to look at trees (interact with the

column) will move more slowly. People who run straight through (don't interact)

will move faster. Because each person has a different level of interest in

trees, they will exit the forest at different times, thus becoming separated.

The HPLC column is that forest, designed to create differences in the travel

time for each compound.

Technical Definition: An HPLC column is a stainless-steel tube tightly packed with very small, porous particles (the stationary phase). These particles have a specific surface chemistry that interacts with the chemical compounds (analytes) in your sample as they are pushed through by a liquid (the mobile phase).

Key Components of an HPLC Column:

- Column Hardware: Typically,

a stainless-steel tube capable of withstanding high pressures (up to 1000

bar or more in UHPLC).

- Stationary Phase: The

packing material inside the tube. This is the most critical part that

defines the column's selectivity. It consists of:

- Base Particle: Usually silica or

polymer beads, typically 1.7 to 5 micrometres in diameter. Smaller

particles give higher efficiency but require higher pressure.

- Surface Chemistry: A layer of molecules chemically bonded to the base particle. This layer determines how the column interacts with your compounds. Common types include C18, C8, Phenyl, etc.

HPLC Column Selection Guide

Selecting the right column is the most critical

step in developing an HPLC method. There is no single "best" column;

the choice depends entirely on your sample.

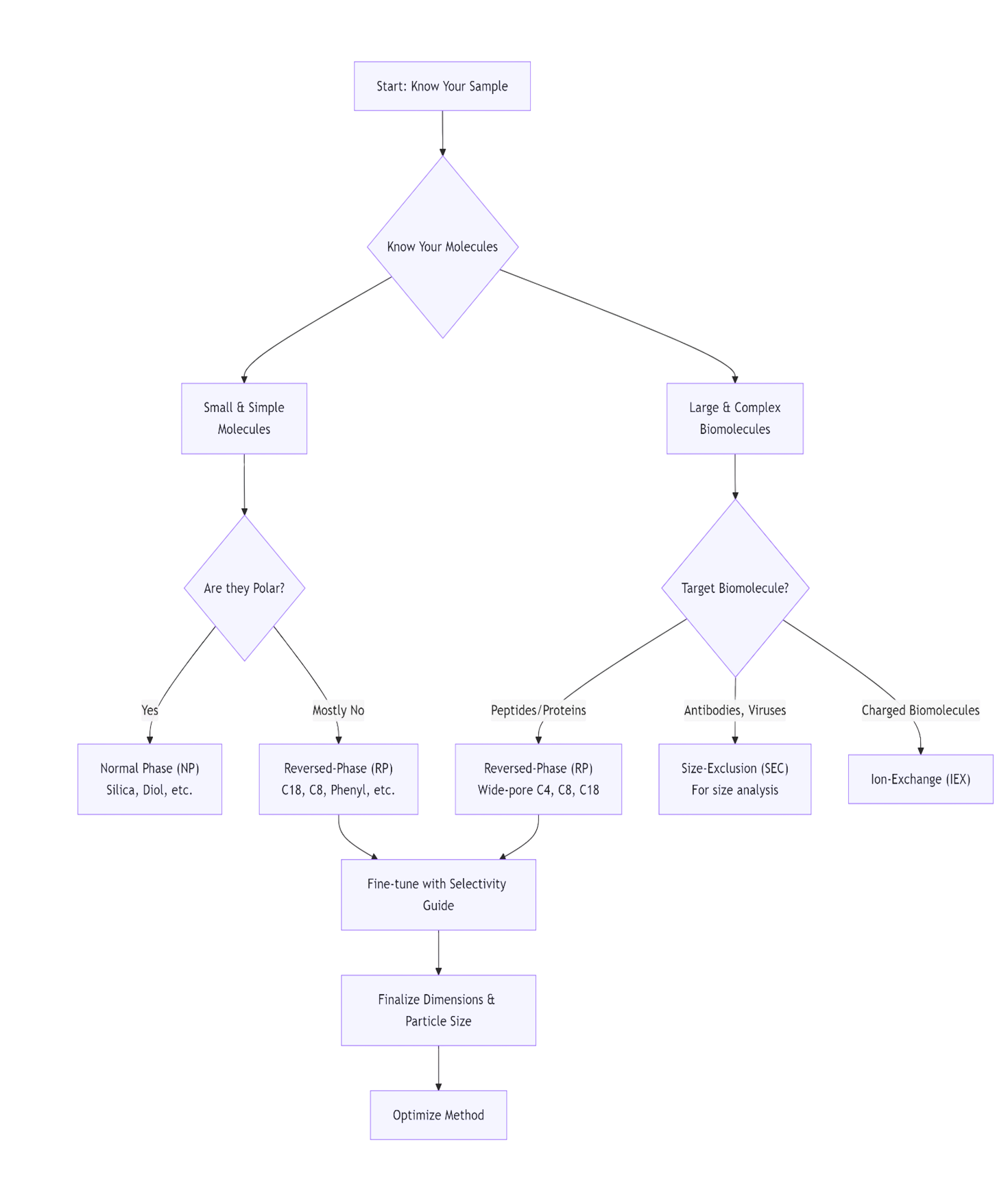

Here is a step-by-step guide to selecting an HPLC column, summarized in the flowchart below:

Now, let's walk through each of these steps in detail.

Step 1: Understand Your Sample and Goal

This is the "know your enemy" step.

- What are the compounds? Their

chemical structures, molecular weights, and functional groups.

- What is their polarity? Are

they hydrophobic (non-polar) or hydrophilic (polar)?

- Are they ionic or ionizable? Do

they have acidic/basic groups?

- What is the sample matrix? (e.g.,

plasma, soil, food extract)

- What is the goal? Qualitative

analysis, quantitative analysis, or preparative purification?

Step 2: Choose the Separation Mode (The Big Choice)

This decision is primarily based on the polarity and size of

your analytes, relative to the sample matrix.

- Reversed-Phase (RP)

- Mechanism: Partitioning between

a non-polar stationary phase and a polar mobile phase.

- Stationary Phase: Non-polar (e.g.,

C18, C8, C4, Phenyl).

- Mobile Phase: Polar (e.g.,

Water, Methanol, Acetonitrile).

- Use Case: ~80% of all HPLC

applications. Ideal for non-polar to moderately polar,

water-soluble molecules. Excellent for pharmaceuticals, food analysis,

environmental samples.

- Elution Order: Most polar

compounds elute first, most non-polar last.

- Normal-Phase (NP)

- Mechanism: Partitioning between

a polar stationary phase and a non-polar mobile phase.

- Stationary Phase: Polar (e.g.,

Silica, Cyano, Diol, Amino).

- Mobile Phase: Non-polar (e.g.,

Hexane, Chloroform, Ethyl Acetate).

- Use Case: ~10% of

applications. Ideal for highly polar, water-insoluble

compounds, isomers, and chiral separations.

- Elution Order: Most non-polar

compounds elute first, most polar last.

- Ion-Exchange (IEX)

- Mechanism: Interaction between

charged analytes and oppositely charged groups on the stationary phase.

- Stationary Phase: Charged

groups (e.g., -SO₃⁻ for Cation Exchange, -N(CH₃)₃⁺ for Anion Exchange).

- Use Case: Separation of ions,

proteins, nucleotides, sugars.

- Size-Exclusion (SEC)

- Mechanism: Sieving of molecules

based on their hydrodynamic size (not molecular weight directly).

- Stationary Phase: Porous

particles with a specific pore size range.

- Use Case: Separating proteins,

polymers, and large biomolecules. Also, for desalting.

- Elution Order: Largest molecules

elute first, smallest last.

Step 3: For Reversed-Phase (The Most Common

Scenario), Follow the Selectivity Guide

Since RP-HPLC is so dominant, here’s how to choose within this category:

|

Stationary Phase |

Key Characteristics |

Best For |

|

C18 (ODS, L1) |

Gold Standard. Highest hydrophobicity, greatest retention. |

General purpose, non-polar to medium-polar

compounds. |

|

C8 (L7) |

Slightly less hydrophobic than C18. Similar

selectivity. |

Good for molecules that are too retained on

C18. Often used for peptides and proteins. |

|

Phenyl (L11) |

π-π interactions with aromatic rings.

Different selectivity than alkyl chains. |

Aromatic compounds, isomers. |

|

Phenyl-Hexyl |

Combines π-π interactions of phenyl with the

hydrophobicity of a hexyl chain. |

A great alternative to C18 for different

selectivity. |

|

Cyano (CN, L10) |

Weak hydrophobicity, slightly polar. |

Can be used in both Reversed-Phase and

Normal-Phase modes. Good for polar analytes. |

|

Pentafluorophenyl (PFP) |

Strong π-π interactions, dipole-dipole

interactions, and shape selectivity. |

Excellent for separating complex mixtures of

isomers (positional, structural). |

General Rule of Thumb: Start method development with a C18 column. If the

separation is poor, switch to a column with a different selectivity (e.g.,

Phenyl or PFP).

Step 4: Choose Column Dimensions and Particle Size

This affects efficiency, speed, and pressure.

- Length (L):

- 50-150 mm: Standard for most

analytical applications. Good balance of speed and resolution.

- >150 mm (e.g., 250 mm): Higher

resolution for complex mixtures but longer run times and higher pressure.

- <50 mm (e.g., 30 mm): Fast

analysis for simple mixtures, lower resolution.

- Internal Diameter (ID):

- 4.6 mm: Standard analytical

column.

- 2.1 mm: For LC-MS (better

compatibility, lower flow rates).

- 1.0 mm and below: Micro/nano-LC

for limited samples or specialized MS.

- Particle Size (dp):

- 3 µm to 5 µm: Standard for HPLC.

Good efficiency and pressure.

- <2 µm (e.g., 1.7-1.8 µm): For UHPLC.

Higher efficiency and faster analysis, but requires instruments that can

handle very high pressure.

Summary & Quick-Start Guide

- Unknown Sample? Start with a Reversed-Phase

C18 column.

- Common Starting Dimensions: 150 mm or 100 mm long, 4.6 mm

ID, 5 µm or 3 µm particle size.

- If compounds are too retained (elute too late), use a weaker mobile

phase or a less retentive column (e.g., C8 or Cyano).

- If compounds elute too quickly (no retention), use a stronger

mobile phase or a more retentive column (e.g., C18).

- If you have poor resolution between peaks, try a column with a

different selectivity (e.g., Phenyl or PFP) or adjust the mobile phase

pH/organic modifier.

- Always check the literature! Someone

has probably analyzed something similar to your sample. Start with their

conditions.

By following this logical process, you can systematically narrow down the vast world of HPLC columns to the few that are most likely to work for your specific application.

Leave a comment